In this ongoing series featured every month, “Day & Night” focuses on individuals who have impacted the world of haute horlogerie positively… This month, we are back in Switzerland via erstwhile Yugoslavia tracing the life and passions of Miki Eleta, the clockmaker who was responsible for the creation of a whole new category in the GPHG awards

In 2021, Miki Eleta’s clock Svemir (Universe in Serbo-Croatian) was a prime contender for the GPHG Mechanical Exception Prize, though ultimately the winner in that category was Bvlgari Octo Finissimo. But it paved the way for the introduction of a new category “Mechanical Clock” described on the GPHG website as “mechanical time-measuring instruments, such as longcase clocks or table clocks”. A true Renaissance man, Miki has mastered several arts and crafts in his meandering path to clockmaking. What is truly astounding is that most of his skills are self-taught…

Lucky childhood

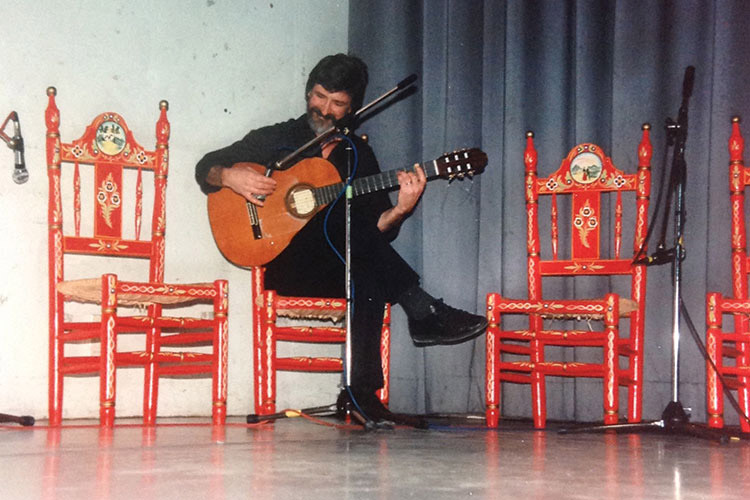

Born in 1950 at Visegrad, Bosnia-Herzegovina – which was then still part of Yugoslavia – Miki had a great childhood in Yugoslavia and describes it as a “lucky childhood”. “From the age of six, I was interested in music; I was fascinated with the guitar and the music of the flamenco.” Growing up, Miki attended the local gymnasium and on leaving school enrolled at the University of Sarajevo to study social science.

“But I never actually worked in that field of social sciences. After finishing university, at the age of 23, I made my way to Switzerland because I wanted to earn some money so that I could buy a guitar.” Miki’s sister was already living in Switzerland at that point and so Miki could travel down from Yugoslavia easily.

Good times

It was in Switzerland where Miki was working as a nurse’s aide that he met his future wife Elisabeth who was working as a nurse in the same hospital. That was 48 years ago, and Miki describes the 48 years as a ‘good time’. They got married soon after and the children followed quickly. Miki left the field of health care when he opted to stay home and look after their children while his wife went to work. Once the children had grown up a bit, Miki started exploring his interests.

A great guitar player, Miki was able to get his first guitar in his early 20s. Soon after, buying his guitar, he and his wife took off to Spain twice, where they lived for short periods. While Elisabeth learnt Spanish, Miki learnt to play music for the flamenco. Following that, for 20 years, Miki accompanied flamenco dancers on his guitar. Music is a lifelong passion, and in his musical clocks, he combines his love of music, haute horlogerie and automatons.

Variegated creations

As the children grew up, Miki started making wooden creations. He first started by restoring antiques and was very successful. A friend once commented, “If I had such gifted hands, I would start my own atelier and work for myself.” This prompted Miki to take the plunge and begin his own atelier for creating furniture by 1990. “Because my wife was working throughout, I did not have the burden of supporting my family financially and I could afford to take the risk of being independent, in those early days as a craftsman.”

Six years later, Miki was asked by a company to build a machine for their galvanic factory. Needless to say, Miki again learnt how to build a machine by himself as he had earlier learnt how to restore antiques and create furniture. A very quick learner, Miki was also great with his hands – this combination meant that it was easy for him to master new crafts and skills.

Talking about the bewildering variety of things he has done, Miki explains that he just follows his ideas. “Once, I get an idea, I think about how to make it. If I lacks the skills or knowledge to make something, I seek out experts in that field, ask them and learn quickly to master that skill.”

Making that single galvanic machine was a game-changer for Miki. Prior to that, Miki was firmly against the idea of ever working with metal. But once, he actually started working with metal for the machine, he had so many ideas for things that he could make with metal ; it made him realise how much he loved working with metal, and this led to his interest in kinetic art in metal.

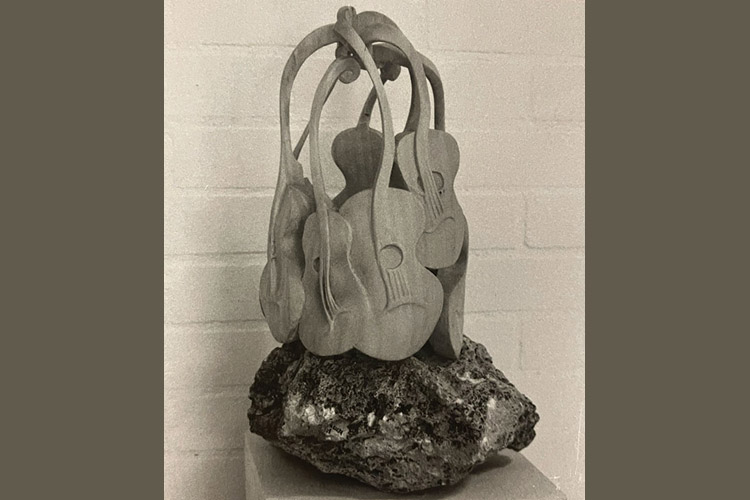

Kinetic art

Miki describes his life as phases; “I do not make the jump from disparate fields; somehow working in one field actually pushes me into a totally different field. It is not I who determines to do this or that. My interest leads the way.” Soon, he was making kinetic sculptures – artworks that move – from recycled and new materials of all kinds. Miki’s kinetic art pieces were a great success, and he has created around 80 pieces of kinetic art – either to be hung on walls or to be placed outside, including ten major kinetic art pieces that are displayed in various cities.

Clockmaking

In the late 1990s, Miki was restoring not only antique furniture but also clocks. In 2001, a client questioned the accuracy of his restored clocks. He said, “You cannot build this kind of machine accurately as you do not have the necessary knowledge to do this”. He was wrong, of course, as the clock did work accurately. A stung Miki challenged the visitor; “Come back in one year and you can see a clock that I have created, which will be highly accurate”. Miki decided on a clock for the challenge as that is the most accurate measuring device. In the following year, Miki was relentless in his quest to learn clockmaking.

“My first clock was the ugliest thing I ever created, but I was able to sell it for CHF 7,500. Everything was new to me, and every single thing was problematic. Calculating the number of teeth in the gears was a big problem as I never liked mathematics. I knew a watchmaker and every time, I ran into a problem for which I could not get a solution, I would seek his help. He was very kind and helped me figure out solutions. I went step by step. I read up a lot on watchmaking. But the whole journey was quite difficult as I was more than 50 years old when I started watchmaking.”

It took Miki less than a year to make his first clock. Sadly, the man whom Miki had challenged to come back in a year to see his watchmaking skills never came back. “I really would love for him to see the pieces that I make now,” says Miki with a smug look. “Initially, I mostly made clocks; sometimes, I did create fountains on orders, but my interest was in clocks and later automatons.”

“In the early days, orders came from people in Switzerland, from people who knew me. I then started displaying my clocks at exhibitions. Sometime later, in 2006, a friend suggested that I should get in touch with AHCI Academy (Académie horlogère des créateurs indépendants). In 2008, I became a member of the Academy and from then on, I started attending Baselworld and exhibiting there every year.”

The response from the public has always been good, and every year, people came to see Miki’s creations as each year, he exhibited something new and different. “All of the Academy members usually exhibit together in a common space and so there was a lot of interest as every single watchmaker’s works attracted aficionados; thus, I got new clients.”

His wife Elisabeth explains Miki’s initial days as a clockmaker, “I was still working as a nurse when he started working on his first clock. He would work in the morning when I looked after the children. In the afternoon, I would go for work, and it would be Miki’s turn to take care of the family. We divided our responsibilities to the family, and it was good for the children to have both parents spending quality time with them.”

While lots of orders came in, there have been numerous instances when Miki had made a clock just because he wanted to. Miki prefers to work on his own ideas for clocks rather than create bespoke timepieces. He then exhibits them to find a customer and is usually able to sell them, but sometimes people came to him with specific requests. “For instance, there was a man who wanted a clock made for his daughter to celebrate her becoming an adult. I learnt what was the girl’s favourite animal, colour, and flower and then let my imagination take over. I was able to give my creativity a free rein and the girl was delighted with what I had created.”

“One of the weirdest order I ever received was when someone from Oman ordered a clock to be presented to their ruler. They gave the order and when I was midway through making the clock, they came over to stay here in Zurich. They would come to my workshop every day and kept asking for changes all the time. This was highly disturbing to me as I couldn’t concentrate on my work; I finally had to ban them from my workshop. I need a silent atmosphere so that I can immerse myself in my creation.”

Automatons

Miki’s creations do not just tell time; they are a combination of clocks, automatons, and chimers with most of his creations giving off either a fairy-tale or alien vibe. “As I spend more time on working with clocks, I find myself delving more into philosophical concepts of time, and of life. The man who is looking at his wristwatch should realise that he is ephemeral, but time is eternal. I try to give shape to this concepts in my work; for instance, through my Minute Eater, I want to say, ‘Life is beautiful, enjoy it, because every minute you waste, you lose a minute of your life’. Every one of us has an animal like that within us that eats our minutes. I want to remind people that they should enjoy life; time is a gift. The Minute Eater is not just a clock; it is a philosophical statement.”

Exhibiting at M.A.D Gallery

“Maximilian Büsser, founder of MB&F and M.A.D. Gallery (which stands for Mechanical Art Devices), had seen my work at Baselworld and liked them. He came in search of me in 2012 and asked if I would be interested in exhibiting at the Gallery. Max is the kind of person who is interested in highlighting the works of new artists and watchmakers and encourage them. Showing my work at the Gallery has definitely proved to be a step up the ladder for me, and it was Max who paved the way for me being able to attend Dubai Watch Week.”

One-man army

He always worked by himself and has never had anyone else helping him or working on his clocks. When asked about who takes care of after-service or repairs, Miki proudly explains, “Almost none of my work has needed any kind of repairs till now. Only one clock that was sold to someone in Germany has had problems, which were present since the beginning. I had to go there 2-3 times, before I could fix the error.”

Work-life balance

Miki works on his creations every day from morning till late night, but he is also a person who knows how to enjoy and live his life. If any of his grandchildren – he has 4 of them – are visiting, then work goes for a toss; “Life is more important than anything else. I have a big garden; whenever, I have any problems or am stuck in my work, then I spend time in my garden. Gardening helps me clear my mind and thinking and I usually get my solutions. I have my own way of working.”

What next

The pandemic meant that Miki could not sell anything as he was not able to exhibit anywhere, but it was also good because it gave him a lot of time to create. I think I have found my niche after wandering through so many fields. I may work more with metals, but I shall probably stay in the field of clockmaking and create many more beautiful objects.

“My grandchildren love to come with me to my workshop and even lend a hand sometime, but nobody is interested in it as a career or future. My grandchildren are part of a family of circus entertainers and currently, they are keen on going into the circus.”